BLOOD AND BLUE RIBBONS: Chp. 25

A STORY OF THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

My Memories Of Events From The Great Battle Of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

June 30th – July 3rd, 1863

Abigail Daniels, Summer, 1865

A Novel

Copyright by Elyse Cregar

Friday, July 3rd, 1863

Early Afternoon

A Moment of Joy, A Plunge Into Darkness

Without the weight and worry of my brother, I quickly made my way down the path to a clearing. Stopping for a moment and closing my eyes, I let the hot sunshine warm my face. When I reopened my eyes, I felt a moment of joy. I had never seen such an intense blue sky nor such pure white billowing clouds. A hawk circled in the distance. Yellow butterflies danced on a bush near my hand. I felt the sun begin to dry my damp clothes.

I shouldered Kit’s musket and tied his jacket around my waist. Stuffing his kepi cap into the single trouser pocket and checking that the scrap of Maine flag was still there, I splashed into the creek up to my knees. As I bent to wash the grime off my face and hands, my laced shoes sank into the muck. I stared at my reflected image, which revealed a face caked with grime. My hair hung in strings and knots; the netting long gone. Strips of fabric dangled from the shirt I wore where thorns had torn it last night. I can scare off the entire Rebel Army!

I bent closer to the water and put my hands in the stream. The creek delivered new evidence of battle: knapsacks, ammunition boxes, bloody shreds of clothing and boots circling in shallow pools until they snagged in the overhanging branches. Not daring to linger, I climbed up the bank and used a few drops of canteen water to wash my face and hands.

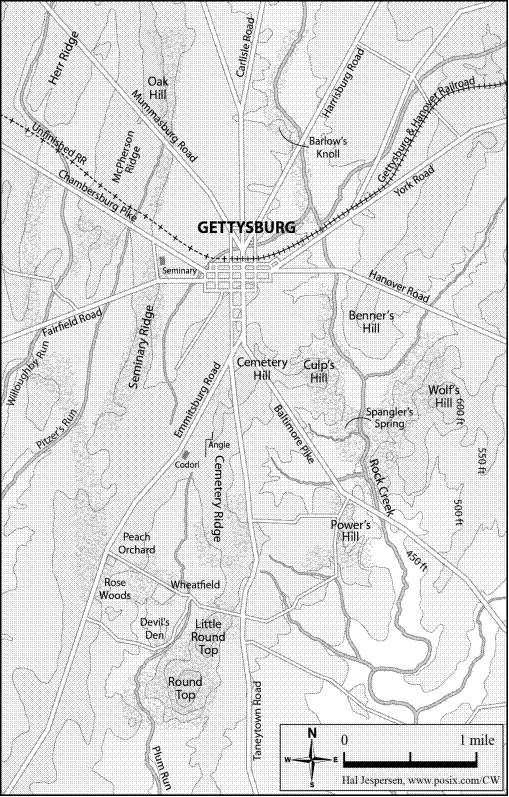

Within minutes I reached the Baltimore Pike. Wagons rumbled past me. Mounted officers directed the movements of hundreds―no, thousands―of infantry troops from one spot to another along the gentle ridge to the west. But not once did I see or hear enough to tell me whether the Union Army had won.

Turning north I walked toward town, a shorter distance then the walk to the Miller farm. I was determined to reach home, even as my soggy feet developed blisters in my wet shoes.

As lines of Union ambulance wagons moved south, I was often forced to stand aside for their passage. The cries of the wounded filled the air. The wagons left a bloody trail. Blood pooled in the ruts of the road. Every barn and house along the way displayed the green and yellow flags of hospital quarters. Citizens and soldiers brought wounded men in or bodies out.

In the distance I could see the twin towers of Evergreen Cemetery Gate House, the home of the Thorn family. Several groups of men sat in sunny fields eating lunch. My heart surged with hope. How could they be enjoying a picnic if the fighting was not over?

But when I saw long lines of gray uniforms gathering a mile away along the Lutheran Seminary Ridge my heart sank.

I climbed up on a rocky outcrop to assess the activity. In addition to the nearby Union ambulance wagons, there were rows of ammunition wagons, horses hauling cannons into place along the ridge near the cemetery, men in blue everywhere around me cleaning weapons, gathering, and buzzing like workers in a hive. Officers on horseback rode among them, directing them to this or that position. I was over-awed by the sight of these blue-clad hordes.

“Excuse me, Miss, but what regiment are you in?” asked a young officer, pointing to the gun hanging from my shoulder.

I jumped down.

“I borrowed this musket from a friend. I had to rescue my little brother.”

“Here, you must allow me to take it, Miss. That gun is army issue and better used by one of our men.”

He held out his hand. “We’re going to need every gun we can get.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, as I reluctantly slipped Kit’s musket from my shoulder. “I thought the fighting was over. I’ve heard nothing for hours.”

The officer took the weapon and pouch from my hand.

“Sorry to disappoint you, Miss. But the fireworks have barely begun. Johnny Reb is gathering his legions out on that far ridge, about a mile west of here.” He pointed to Seminary Ridge.

“But the cannons stopped firing on Culp’s Hill!” I argued, as if I could convince this soldier that the battle had ended.

“Our Twelfth Corps kept that hill. Those rebs did not make much of a dent on our right last night and they finally gave up. Excuse me, Miss. You had best find some shelter. Maybe you can help in one of the field hospitals behind our front lines.”

“You mean I can’t go home to Gettysburg?” I blinked back sudden tears.

“I’m afraid not, Miss. Our own men will not allow you near town, and even if they did, you would get shot by a reb sniper. The Confederates still occupy the town.” He studied me for a moment.

“Your help with our wounded men would be greatly appreciated, Miss. We expect the rebels to concentrate their attack on our left or right flanks. That mile of open wheat fields between us should greatly discourage a frontal attack on our center, but we are preparing for anything. The rebels may even hold off an attack until tomorrow.”

He looked kindly at me. “Please take shelter as soon as possible, Miss.”

I turned away from the officer. Despite the man’s advice, I continued walking toward Gettysburg. I passed a barn on my right. Ambulance wagons were stopped near the barn while men and women unloaded one stretcher after another. I stared at the activity for a few minutes, then kept walking with my head down, refusing to take part in any more amputations.

As I approached the Cemetery Gate House, I had to weave my way through a tangle of more ambulance and supply wagons. The cacophony of cries from the wounded made a mockery of the sunshine. Horses were restive, often pawing the ground and snorting. Perhaps they could smell what was coming. I recognized a woman from town as she tossed out a pile of bloody rags from the second floor of a barn set back off the road.

I stood in the middle of the Baltimore Pike, racked with indecision. As close as I was to the outskirts of town, I realized that the soldier who took Kit’s musket was right. I would never be allowed through the barrier.

It would be at least a two-mile walk to Mary Ellen’s farm, but I could bake bread to bring to Joe Pye and the others. Perhaps the Confederates would no longer be lingering near Rock Creek since they had given up their fight for Culp’s Hill. And poor Joe Pye; how hungry he and the other children were when I had left them. I gazed sadly one last time across the gentle ridges toward home, turned and began walking into the woods for shelter from the sights surrounding me. I knew I should help with the wounded but I first needed to find food for the children. The closest hope was the Miller farm.

My last conscious memory was of the feeling of my body being thrown like a limp rag into a nearby ditch. With the wind knocked out of me, I could not draw another breath, could not hear anything but a terrible roar.

***********************************************************

Hal Jespersen volunteered his time and expertise in creating the accompanying map of Gettysburg. You may see more of Hal’s carefully drawn and extensive collection of maps at his website cwmaps.com

NEWS FOR FOR MY READERS OF BLOOD AND BLUE RIBBONS: I hope to publish this story as an ebook this summer! Please watch for further updates on this space!

The FREE chapters to follow will post on my Substack Section: Blood and Blue Ribbons, generally on Saturdays and Wednesdays. This novel appears as a Section on my Substack site: MORE CATS, PLEASE!

Post for Wednesday, June 4: Chapter 26

To read more about the Battle of Gettysburg, please visit my non-commercial website: Bloodandblueribbons.com . There you will find a brief history of the Maine 16th Volunteer Infantry Regiment at Gettysburg on The Stories tab.