BLOOD AND BLUE RIBBONS: Chp. 17

A STORY OF THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

Blood and Blue Ribbons

My Memories Of Events From The Great Battle Of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

June 30th – July 3rd, 1863

Abigail Daniels, Summer, 1865

A Novel

Copyright by Elyse Cregar

Thursday, July 2nd, 1863

Midafternoon

Promises

As I entered the gate to my own backyard I paused at the well. A fleeting memory of Lee’s strong arms and gentle hands at the pump handle filled me with longing.

Walking up the back steps, I heard familiar conversation coming from the kitchen. Old Solomon was sitting at the table while my mother served him a bit of bread and jam.

My heart tightened as I observed the change in him. His long white hair and beard were matted with grime. The familiar twinkle of his blue eyes had disappeared. His cheeks appeared to be even more gaunt than usual, and his hands shook as he picked up his cup. Why, he is too old to be carting wounded men around in this heat.

“Hello, Ma. Hello, Solomon,” I said, offering a cautious smile.

“Abigail, we have been worried about you. I trust you have managed to keep out of sight of the Confederates.”

Her voice was laced with meaning. Then she began to reach out her right hand toward me. But Ma withdrew her hand and placed it on the old man’s shoulder, as if this were its intended destination all along.

“You see what I mean,” she addressed Solomon. “My headstrong daughter has been out roaming the town while it’s filled with enemy soldiers, and I have been attending to our wounded men. She may as well go back with you as stay here. I can care for our men by myself.”

“Ma!” I protested. Lee’s promise! My lips still warm from his kiss.

“Abigail, you will do as I say. Solomon says every room of the Miller house, as well as their barn, is filled with mostly Union wounded men. You can do more good there.”

“I just came from our church, Ma. There must be hundreds of wounded men there and in the other churches as well. The Confederates are looking for more places to put the wounded. I can help in the churches. I have helped!” I added forcefully.

My mother shook her head. “I think you’d be safer out of Gettysburg, away from the sniper fire.”

“I helped a doctor amputate a man’s leg. I held a dying boy.” My voice trailed off when I saw the look in my mother’s eyes. So that was it. My arguments were futile. I lowered my eyes; my face grew hot with anger.

“Very well, Mother. If that’s what you think best.”

I felt a brief surge of joy at the thought of seeing Mary Ellen again. Even in this tense moment my mind spun with a reckless plan for later. Perhaps I could borrow Betsy for a ride to town tonight.

“Get your things, Abigail,” Solomon said. “You may be with us for a while. Our soldiers are massing around the ridges south of town. I believe there will be quite a row today. We must return to the farm as soon as possible.”

“Do you have wounded men in the wagon?” I asked.

Solomon shook his head. “Too many rebels watching every move. I wanted to see how you and your ma were handling things.” He winked at me. “I know the shortcuts around town those rebels don’t know.”

“Solomon, you’re not telling the whole truth, are you?” Ma asked. “You’ve been out in the fields, haven’t you? Looking for Willie?”

The old man put his head between his gnarled hands and stared at the floor. His voice broke.

“I’ve turned over more bodies than I can count. Willie must be alive! But the wounded men out there are crying for water. My Lord, the rebels have abandoned their own as well as the Union men. And in this heat!”

“We can only pray that Willie is alive and with his comrades behind the Union lines. There is nothing more you can do, Solomon. You must return to your own family, and Abigail will be of help to you.”

“Ma, I forgot to tell you about the Union officer hiding in a pig shed. General Schimmel . . . Schimmelfenning! I promised to bring him food and water!”

“General who? Are you making this up?”

“Of course not! He escaped capture yesterday by hiding in a smelly old woodpile near Baltimore Street. I found him early this morning when I was searching for water.”

Ma stared at me. “Well, there’s nothing you can do for him now,” she said stiffly. “He’s too close to the snipers.”

My anger took over. “You think the only men who need care are those nine men in this old attic! You found them and they are yours! Well there are about ten thousand other men who need help right here in town, Ma! And I promised the general I would return with food and water.”

“I know about your promises,” my mother said bitterly. “You keep promises between you and the rebels.” Her eyes gleamed. “Or should I say, a certain rebel?”

I was speechless. Ma’s anger was as raw and deep as some of the wounds I had seen that morning. I turned to Solomon, as if he would understand my distress.

Solomon’s eyes had darted from one to the other of us during this exchange.

“Enough of your sparring, you two. We got us a war right here in Gettysburg, a bigger war than the one in this kitchen. Now, Abigail, I will take you to this general on our way to the farm, but only if we can approach safely. You gather up what you need!”

I picked up a tin cup, noting the two full buckets of water in the kitchen. Solomon must have helped my mother find the water. I dipped the cup into one of the buckets and drank, knowing better than to ask for one of the buckets for the general. I gathered three apples and a fresh loaf of bread from the pan.

“I’d like to bring some coffee for the general, Ma. I will put it in a small bowl. I’m certain he would appreciate it.”

Ma simply nodded.

“Solomon, take more bread for your family.” She handed him three warm loaves.

“Goodbye, Ma,” my voice unsteady.

“I will pray for you,” my mother began sternly, but as her voice softened, I saw the moisture forming in her eyes.

Together Solomon and I put our supplies in the wagon bed, a mess of bloody blankets and hay.

Confederates lounging in nearby doorways stared at us as Solomon clicked at Betsy. I wiped my brow of sweat and looked straight ahead, hiding my shaking hands into the folds of my bloodied apron.

“Where be this general of yours?” Solomon asked.

“He’s in a woodshed south of here, through this alley,” I whispered. “But don’t bring the wagon up too close. Maybe stop by one of the hospital buildings, where the green ‘H’ flags are hanging.”

I pulled a stained white cloth from the wagon bed and gave it to my friend.

“Here, hold this high. Perhaps the Confederates will think you’re helping with their own wounded.”

Solomon nodded. He guided Betsy carefully toward the south of town. I wondered how much my mother had revealed to the old man.

The sniper fire continued sporadically, but I was almost used to it. The sharp exchanges no longer frightened me as much as other events in my recent past. I thought it barely possible that a bullet could pierce me in anyway more painfully than I had already been pierced. My mother must be terribly angry with me, I thought. And I knew I had done nothing wrong. How unfair it all was. Now I was being banished from her sight.

“Please, Solomon, stop here.”

Solomon pulled Betsy up at the end of a long line of ambulance wagons in front of a large brick home.

“The shed is close by. I will hurry.”

I wrapped the bowl, bread and apples into my skirt and climbed down, careful not to spill the precious coffee.

“Be careful, Abigail.”

Looking around to see if anyone watched, I slid around a building into a narrow alley. I hurried down the dusty track to the general’s hiding place, where I found him just as I had that morning, coughing and muttering.

I peeked into the small opening and waited for my eyes to adjust to the darkness.

“General, I have brought you some warm coffee, bread and apples. I did not forget my promise.”

“My goodness, young madchen. You are an angel and perhaps even a saint. Bless you!”

The general grinned as he took the supplies. He gulped the coffee, then began on the bread. Bits of crust fell on his beard.

“Madchen, can you please fill this empty bowl with the well water? Ja?”

I hurried to the well while glancing around to see if my movements were being observed by anyone in the upper windows. I pumped the handle a few times until the water splashed over the top of the bowl and brought it back to the general.

“I could not bring a bucket. Ma needs the buckets for the wounded in our attic.”

“Ja, ja, Miss. This vill be very fine. Ja gut!”

He drank the entire bowl down. I watched his Adam’s apple bobbing as the precious liquid ran in rivulets into his beard and down his neck. He poured the last few drops into his hand and wiped his face.

“Danke, danke. You haf saved my life, meine kleine madchen. Du bist sehr mutig. You are very courageous.”

He smiled and took my hand. “My hands smell like dieser schweine!” He coughed again, more hoarsely than before.

“I wish you could come with us,” I said. “Old Solomon is taking me south of town where it’s safer. He has a farm down on the Baltimore Pike.”

“Das ist gut, Miss. You vill be an angel wherever you go.”

“Not everyone around here thinks I’m an angel, General.”

“Nein?” He sounded surprised. “Tell me who und I vill court-martial that person.”

I laughed.

“Shhh.” He put his finger to his lips. “The rebels vill think perhaps you like to talk mit dieser schwein.”

I turned my head at the sound of nearby sniper fire, seeming louder than before.

My new friend handed me the empty bowl. “Could you fill this once more, bitte, then you must go.”

I brought the bowl to the well and filled it; my mind full of the many questions I wanted to ask my friend. He was so easy to talk to, even with his German words and accent. I walked quickly back to the pile of logs and handed him the bowl.

“I don’t know when I will be back, but I will bring more food as soon as I return to town.” I hesitated. “General, can I ask you one question?”

“Ja, naturlich.”

“If a Confederate soldier doesn’t believe in slavery, well, why would he fight for the South?”

“That would not be easy to answer in a woodshed mit the schwein. Dear kleine madchen, this terrible war must end die knechtung, ahh, the enslavement of other human beings. It must end! These southerners, they vant only to keep their free labor and their cotton profits.”

He spat into the dust, then took another sip of water.

“I haf met no rebel soldier like you are telling me about. Ve vill talk more on this someday, ja? Now tell me, Miss, where do you live? Please, I vant to thank you properly when this fighting is over.”

I described my house on West High Street. Perhaps Ma would believe me if General Schimmelfennig came personally to our house.

I could imagine the general telling my mother what an angel her daughter was, how she had possibly saved his life. And what would my mother say?

“Goodbye, General.”

Gathering my skirt and apron, both now more soiled than ever, I stood up outside the shed and wiped the wettest mud and dried blood from my apron, my question unanswered. Forcing myself to focus on a simpler matter, I stared down at my filthy clothing. I should have taken my last clean dress with me, but perhaps Mary Ellen would have one I could borrow. I stole a few more seconds to wring my skirt under the well water.

Ignoring for a moment the immediate danger surrounding me, I ran back to the street where I had left Old Solomon and Betsy.

When I turned the corner, I saw a very tall, very rotund Confederate soldier pushing Solomon away from the wagon. The white cloth fluttered to the ground. The man seized Betsy’s halter and pulled her away from the line of ambulance wagons. Several laughing barefoot soldiers climbed into the wagon bed. The big man climbed up on the seat and slapped the reins.

I ran to Solomon as Betsy trotted off.

“Are you all right?” I asked, breathless.

He nodded and wiped a trickle of blood from his chin.

“Damn rebels!” he spat. “They took your Ma’s bread, too!”

“Oh, I’m sorry, Solomon. If I had not insisted on bringing food to General Schimmelfennig, this wouldn’t have happened.”

“No, you’re wrong, Abigail. It was stupid of me to bring the wagon into town. There are more wagons and horses at the farm but only one Betsy.” He whispered, “Only one Willie.”

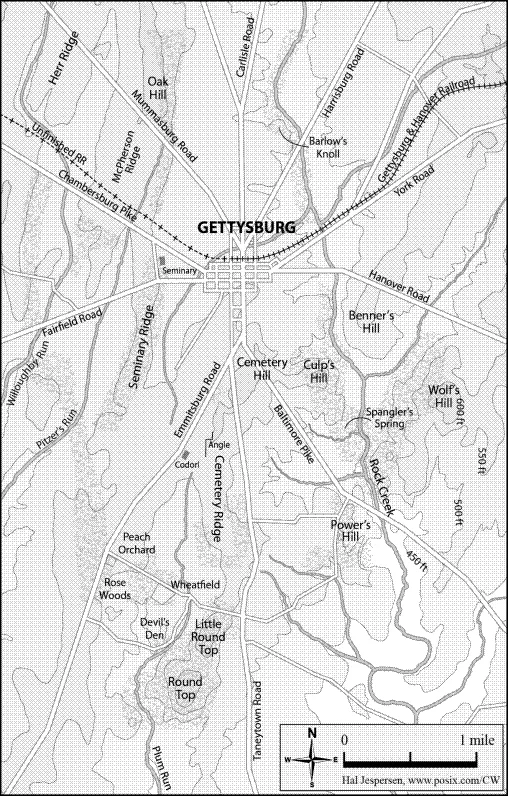

He put his hand on my shoulder. “I know some tricks for getting through the lines. It will be a long walk, longer than the usual three miles, but we do not want to get shot at by our own snipers. We will have to avoid the Cemetery Gate House. Our own soldiers will not let us through even if we survive the sniper fire to get there.”

We both froze at a distant sound. From south of town came the trumpet of bugles and the rhythmic beat of drums.

“It sounds like a parade, not a battle,” I said.

“Whatever it is, we will find out soon enough. We must head north before we go south to the farm. You and I know the trails, Abigail. But we must hurry!”

********************************************************

Hal Jespersen volunteered his time and expertise in creating the accompanying map of Gettysburg. You may see more of Hal’s carefully drawn and extensive collection of maps at his website cwmaps.com

The FREE chapters to follow will post on my Substack Section: Blood and Blue Ribbons, generally on Saturdays and Wednesdays. This novel appears as a Section on my Substack site: MORE CATS, PLEASE!

Post for Wednesday, May 7: Chapter 18

To read more about the Battle of Gettysburg, please visit my non-commercial website: Bloodandblueribbons.com . There you will find a brief history of the Maine 16th Volunteer Infantry Regiment at Gettysburg on The Stories tab.